By Liz Doig, founder and MD of Wordtree

I’ve been interested in cultural change for a long time. When I started to create and roll out tone of voice programmes, I simply assumed that they would have a significant impact on workplace culture.

I remember in a workshop for a financial services company about fifteen years ago, a senior manager said: “What you’re proposing here is profound cultural change!”

“Well yes,” I said. Because why wouldn’t anyone think that a change in language would bring about a shift in the way people thought and did their work?

At that time, I didn’t realise that change was seen as such a big deal in workplaces. My background is in language and communications. It seemed obvious to me that if you fundamentally change an organisation’s language – I mean, really change it, from root to branch – then its culture would have to change too. Language directs culture, after all.

What I didn’t know then was that changing culture and attitudes – and increasing employee engagement – was viewed as a far more worthy and difficult pursuit than simply getting whole teams to write brand-aligned communications.

Dealing with Change Management

My focus was on the comms. I simply assumed the culture would follow (and it did). So I was tracking the success of individual pieces of comms and saying: “Oh yeah, of course,” when the culture aligned with the brand too. Honestly – it seems nuts now, but there you go.

Then I began to realise that changing the way teams engaged with their organisations was something to strive for in its own right. So maybe if we flipped our offer so that change was the big selling point, then great communications could be the nice side effect? And this was when I began to deal with Change Management.

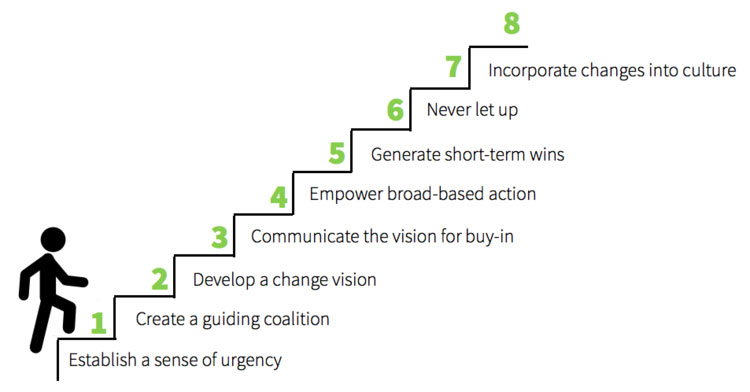

I read a lot of books. I did a couple of business courses. I wrote an essay for one of them on the nature of change in large organisations. Kotter, I thought, was right – but wasn’t it all a bit backward-looking? I mean anyone can look at a successful change in retrospect and say, ah well, yes, that’s because you got sponsorship at senior level, you engaged teams and you brought them along with you – keeping momentum up with good examples of the whole thing working well.

And perhaps the eight-step model does give you a bit of a steer in what the characteristics of a successful change programme should be. But it still doesn’t tell you how to actually do the change, or bring people along.

The lecturer – a professional Change Manager when he wasn’t teaching – thought I was a moron. A moron who couldn’t write properly, to boot (I’m still not sure which hurt more).

“Unless you understand Kotter,” he said, “You will never master change.”

“But,” I said: “Kotter says change is really difficult.”

“That,” said the lecturer, “Is because change is really difficult.”

“Err, well it isn’t really, is it?” I said, “I mean it’s hard work and you’ve got to be organised and be good at involving people… but no way should there be a 70% fail rate.” Mr Change Management Lecturer was less than impressed. “You need to learn to write like an academic,” he added.

Whatevs.

But of course, this has been the prevailing Big Thinking on change. Change is difficult, so people resist it.

I’ve never bought into this. People go through change all the time, willingly. They positively love it sometimes. New cars, new hairdos, new places to go on holiday. If we hated change as much as the discipline of Change Management would have us believe, we’d never buy new technology or try anything for the first time.

And indeed, even when we don’t like the sound of change, we still do it. Or we wouldn’t all be locked down, the majority of us adapting to it rapidly.

Because here’s the thing – change in and of itself isn’t hard. It isn’t something that the majority of people resist. So people not liking change cannot be why so many change management programmes fail.

I think the reason they fail is because they’re all theory and no practice.

It’s like introducing people to yoga by giving them books – and then saying: “Look, yoga is really hard because no-one is doing it.”

You introduce people to yoga by having them do yoga. If they’re really into it, they might read a book as well.

And this brings me back to language. Because language is the way we all practise and normalise change, daily.

For example, we all now know the words for a disease we’d never heard of two months ago. We all now know what being furloughed means. We know what social distancing and self-isolation are. And by practising these words, we adopt the change itself. A concept without accessible language cannot be adopted easily. A concept that’s easy to describe, on the other hand, is shared and adopted.

On top, language is something we all use daily. And if we have to examine the language we use and change it or augment it, our behaviour is more than likely to follow. It’s because when we examine our words, we automatically have to examine the place they come from – whether we do it consciously or subconsciously.

In workplace culture, these things can – and do – happen:

- If we begin to think legal jargon isn’t acceptable because customers won’t understand it, then we’re beginning to change – just a tiny bit – how we view the purpose of our work.

- If we’ve been told that calling a female colleague “shrill” reflects badly on us, then we begin to consider why that might be – and maybe realise, that despite best intentions, our thinking is a bit sexist.

- If we write forms that talk about “partners” rather than “husbands and wives” or “married couples”, we’re signalling to ourselves as much as to people around us that all adult relationships are valid.

Change isn’t impossible. If the last two weeks have taught us nothing else, it should be this. But theories that aren’t implemented with an easy, daily way to practice change, are empty. To make change real and sustainable, you need a practice that emphasises and reinforces it through daily use. And we say that practice can be language.

Keen to learn more?

Read our blog on nurturing, rather than managing, change

Case study: Find out how we helped to transform culture at Coutts